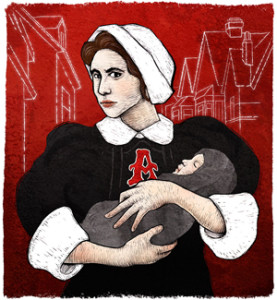

Back in high school many of us read Nathanial Hawthorne’s classic novel, The Scarlet Letter. While the book was published back in 1850, its story is relevant today, but in a new way. Hawthorne wrote about Hester Prynne, a young woman who had a child with a man who was not her husband. As punishment for her sin as well as for refusing to reveal the identity of the illegitimate child’s father, Hester was made to wear a large letter “A” on her chest to forever label her as an adulterer. She was punished by public humiliation in the town square and then made an outcast from society for the rest of her life. Her fate can be viewed as an eerie reflection of what older adults today face—labeled with a capital “A” for aging.

Back in high school many of us read Nathanial Hawthorne’s classic novel, The Scarlet Letter. While the book was published back in 1850, its story is relevant today, but in a new way. Hawthorne wrote about Hester Prynne, a young woman who had a child with a man who was not her husband. As punishment for her sin as well as for refusing to reveal the identity of the illegitimate child’s father, Hester was made to wear a large letter “A” on her chest to forever label her as an adulterer. She was punished by public humiliation in the town square and then made an outcast from society for the rest of her life. Her fate can be viewed as an eerie reflection of what older adults today face—labeled with a capital “A” for aging.

Hester lived in a Puritan settlement in Boston, a repressive community that did not tolerate dissenting ideas. Instead of resisting, she accepted her fate and went on to raise her daughter Pearl on her own, formally set apart from the rest of society. This story haunts me as I reflect on the fate of older Americans who are likewise formally set aside from the rest of society—whether it’s physically when they are placed in nursing homes or emotionally when they live in the community but are repeatedly ignored or patronized.

Despite centuries of enlightenment and progress, we still barbarically isolate select members of society. There is a term I teach my undergrad sociology students: marginalization. It is the systematic exclusion and dismissive attitude toward people who are considered irrelevant and of no value to society. They are stripped of their humanity by those around them. Marginalization happens to minority group members, those with mental or physical disabilities, former convicts, and the homeless. And now we can see it happening to older adults.

Earlier this month, I wrote about this phenomenon of being rendered invisible when I described the Netflix program “Grace and Frankie.” Grace was grappling with being made to think she was no longer relevant simply because she had grown older and worried that she was being erased. Like Hester in the 19th century was for her supposed sin, Grace and so many other aging adults are being ignored simply because they are growing old.

It remains to be seen whether today’s aging adults will quietly accept their fate as Hester did, or fight the insidious ageism the way they fought against racism and sexism years before. In Hawthorne’s story, Hester’s child was named Pearl. Perhaps that symbolism portends a brighter future for us now…one in which aging will come to be seen as a beautiful gift of nature that is valued by all.